*This article was written in 2004

It has been called the “surprise story” of modern missions–the emergence of ‘Christian Africa’ (Bediako, 2000:3-4). In the last century, Christianity in Africa has seen the fastest numerical growth of any continent ever in church history. Down in South Africa, we in the Baptist Union have enjoyed a taste of this rapid church growth. But such expansion also brings unique challenges. In this article I would like to explore these challenges, first on a wider scale and then zooming in on the BUSA, followed by some biblical solutions and suggested strategies. We must take a hard look at three critical issues that should compel us to launch a church-strengthening movement in the BUSA that will exalt Christ and bless the nations for generations to come.

I. Our Need

Exciting growth

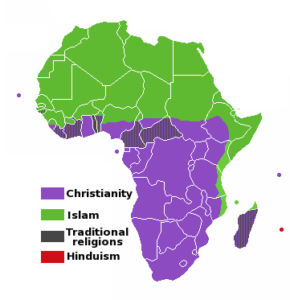

From a continent in 1875 that numbered its Christians in tens of thousands, to a continent with about 8 million professing  Christians in 1900 (10% of the population), Africa now has close to 400 million who profess Christ (48.4% of the population, and 60% of sub-Saharan Africa) (Jenkins, 2002:3; Johnstone, 2001:19-21). Estimates are that at least 4,000 new professions of faith are made every day in Africa, and that this is now the most ‘Christian’ continent in the world (Bediako, 2000:3; O’Donovan, 2000:1). Nearly one in every five professing Christians in the world is an African (Johnstone, 2001:2,19).

Christians in 1900 (10% of the population), Africa now has close to 400 million who profess Christ (48.4% of the population, and 60% of sub-Saharan Africa) (Jenkins, 2002:3; Johnstone, 2001:19-21). Estimates are that at least 4,000 new professions of faith are made every day in Africa, and that this is now the most ‘Christian’ continent in the world (Bediako, 2000:3; O’Donovan, 2000:1). Nearly one in every five professing Christians in the world is an African (Johnstone, 2001:2,19).

In his book, The Next Christendom, Philip Jenkins (2002) states that the heart of global Christianity will not be in Europe or North America, but in Africa. He says, “in 50 or 100 years, Christianity will be defined according to its relationship with that [African] culture” (cited in CH, 2003:2). The August 2003 issue of Christian History “tells the story of sub-Saharan Africa’s ‘Christian explosion’ in the twentieth century—a century that brought Africa from the periphery to the center of the Christian world, largely through the efforts of native African evangelists” (Armstrong, 2003). The inside cover declares, “The rapidity of Africa’s twentieth-century ‘baptism’ was stunning. There’s no better place to see the future of the global church” (CH, 2003:2).

Obvious concerns

Surely this is a cause for rejoicing, for Christ is being proclaimed and the gospel is spreading (Php. 1:18). But there is also cause for caution. Understandably, gospel advances are not tidy and they take place through feeble, imperfect human instruments and often under adverse conditions. Much patience and trust in the Holy Spirit is required in the face of slow progress. Yet this does not erase serious concerns about the way the gospel is advancing in Africa. If Africa represents “the future of the global church,” it is an uncertain future.

African theologian Tienou (1998:6) states: “The evangelical dilemma in Africa can best be described as proclamation without reflection. One observer put it this way, ‘Africa has the fastest growing church in the world: it may also have the fastest declining church!’ Numerical growth far outpaces spiritual depth and maturity in African Christianity”. Tienou (2001:162) goes on to say, “I consider the deepening and the nourishing of the faith of those who identify themselves as Christians [in Africa] to be of the utmost urgency”. Van der Walt (1994:109) likewise warns, “A fat, but powerless Christendom – that is the danger facing us when Christianity grows as rapidly as it is doing at present on the African continent”. Many are now observing that Christianity is shifting southward and becoming increasingly non-Western (Maluleke, 2000:x; Jenkins, 2002:2). But Africa will  also miss the opportunity to set the pace and the example unless her churches are better established in the faith.

also miss the opportunity to set the pace and the example unless her churches are better established in the faith.

Anyone doubting the shallowness of Christendom in Africa need only look at the moral and political chaos in countries where the

vast majority of the population has claimed the name of Christ for years. Probably the most graphic depictions of this nominalism are the horrific genocide in supposedly “80% Christian” Rwanda and the brutal bloodshed in the supposedly “96 % Christian” Democratic Republic of the Congo (Johnstone, 2001:19). Ott (2004) points out, “…the matter of church health in rapidly growing movements has not been adequately addressed. The classic church growth movement was more concerned with numbers than quality. Events such as the genocide among “Christian” tribes in Rwanda, the rampant nominalism and syncretism in Christian churches, are well know problems. … Rwanda is one example of very superficial Christianity having horrific consequences. Another example is the astonishing growth of AICs (African Independent Churches) and various independent movements that are for the most part quite heterodox, but attracting huge numbers of followers; many from established churches.”

Many today view the phenomenal growth of African Independent Churches as promising (e.g., Jenkins, 2002:68-69; Anderson, 2000), while others have exposed the widespread syncretism and false teaching (e.g., De Visser, 2001). As for nominalism, Brierly’s extensive study (Siaki, 2002:47) reports that only 49% of all those in Africa who claim Christianity actually hold membership in a local church. Another study reveals that in Kenya, “80% claim to be ‘Christian’, but only 12% are actually  involved in a local fellowship” (Winter, 1999a:368). It is reported that in South Africa, out of the 30 million who claim Christianity only 6 million regularly attend church (Siaki, 2002:46).

involved in a local fellowship” (Winter, 1999a:368). It is reported that in South Africa, out of the 30 million who claim Christianity only 6 million regularly attend church (Siaki, 2002:46).

Africa is not unique in this dilemma of breadth without depth. While the Western church declines rapidly, many of the churches planted in the ‘mission fields’ remain un-established in the faith (Reed, 2000:73; Johnstone, 2001:13-14). Reed (In preface to Hesselgrave, 2000a:9) warns: “…A growing number of us who were involved in attempting to reshape the missionary enterprise at the end of the twentieth century realize that something is drastically wrong with the contemporary Western paradigm of missions. We see entire movements of churches with an appalling lack of leaders. Almost all of these movements are on course for producing but a nominal fourth generation. Some argue that this downturn is inevitable, yet many of us believe that the biblical ideal suggests that the fourth generation of churches should be the strongest generation to date. With the coming postmodern global village, these churches must be sufficiently strong to realize the potential of fostering a worldwide expansion of the gospel such as has not been seen since the early church.

Possible causes

Ott (2004) attributes this nominalism in Africa mainly to “weak leadership and shallow discipleship”3. When professing Christians quickly revert to pagan behaviour in times of trouble, the gospel is only a veneer and has not penetrated deeply enough to transform their worldview. Van der Walt’s (2002:16) diagnosis is penetrating: “Because the Gospel was not brought as a new, total, encompassing worldview, which has to take the place of an equally encompassing traditional worldview, the deepest core of African culture remained untouched. Christian faith only influenced and changed the outer layers of African culture such as, for example, customs and behaviour. For this reason it often led to superficial Christianity – totally at variance with the nature of the Christian faith, which is a total, all-embracing religion, influencing the whole of life from a reborn heart – in the same way that a heart pumps life-giving blood to every part of the body. The average African convert did not experience the Gospel as adequate for his whole life, and especially not when it came to the most complex issues of life. For that reason we discover all over Africa today that Christians, in times of existential need and crisis, as in danger, illness and death, revert to their traditional faith and view of life. The Gospel has no impact in those areas where it really matters!”

– Tim Cantrell, President and Professor of Systematic Theology, Shepherds’ Seminary

– Tim Cantrell, President and Professor of Systematic Theology, Shepherds’ Seminary